By Ethan Royer

Last month, I related some instances of intentional timber theft. This month, I'll relate a couple of instances of unintentional timber theft and some lessons learned through these experiences.

Timber Spotters

Many years ago, we did custom logging for a grade mill that sometimes purchased timber through brokers, called "timber spotters." These spotters would go around looking for timber and approaching landowners about selling. If the owner was agreeable the spotter would contact the timber buyer who would come and determine the timber’s worth. The mill would then subtract a generous percentage for the spotter and give the owner a bid. The mill would generally sign a contract directly with the owner since it's doubtful the spotter had an Indiana timber buyer's license. In some cases, the spotter signed a contract with the landowner and then sold the contract to a mill.

Engaging the services of spotters is risky and probably even unethical unless they have a buyer's license. It seems the amount paid to the spotter is not fair to the landowner. I know the spotter arrangement caused us a lot of grief while it lasted. We never knew exactly what the spotter told the landowner in an effort to convince him to sell trees. One time a landowner claimed that the spotter told him we would float some logs down the adjacent Wabash River instead of skidding through the property. The river log drives of the old days sound exciting, but sorry, that is one service we just don't offer! I've attempted log burling before but concluded my talents lie elsewhere.

An extremely important part of timber buying is determining if the landowner has realistic expectations about the logging process and the post-harvest appearance of the woods and correcting any misconceptions they may harbor. The spotters we had experience with did not do well at this. They usually high-graded the woods, too.

Incident No. 1

In this incident, the timber spotter arranged the job and sold it to the mill, which contracted us to harvest the timber. We assumed the mill had done due diligence in obtaining permission to harvest timber, marking property lines, and arranging a staging area. However, the "owner" who had sold the timber was in the process of purchasing the property via land contract and did not have the right to sell the timber. After the purchaser had sold the timber, he defaulted on the land contract, and the property went back to the original owner.

You can imagine the rightful owner's consternation when he arrived to discover his trees being harvested! I don't remember how far along the job was when things unraveled, but it was at least partly done. The owner was not pacified by apologies or even the Indiana protocol of reimbursing three times the value of the stolen timber. He sued. As is common with lawsuits, he sued anyone that was involved whether or not they were at fault. He sued the spotter, the mill, and us. We shouldn't have been at fault since we were merely doing the work as the mill had instructed. Yes, I know that's a familiar refrain when something goes awry: "I just work here, I'm not responsible". Yet, it would be redundant and show a lack of trust if the subcontractor always vetted each client when the mill should have done so.

It was a difficult legal situation because we were not the only ones involved. Ideally, it could have been settled out of court, but that isn't how it went. The judge delivered his verdict: we were ordered to pay $13,000. We did not have liability insurance but had provided the mill with a liability statement that promised we would be responsible for what we do. While the mill agreed that we were not at fault, they refused to cover our fine because they reasoned that if we'd had liability insurance, our insurance would've covered it. We paid the fine, but having to accept responsibility for their mistake damaged our trust in them, and we soon found a different mill to cut for. While it was frustrating at the time, it could've been a lot worse. And it may have been a blessing in disguise since we then found more favorable work elsewhere. Some lessons are memorable because they are expensive.

Incident No. 2

Several years ago, we logged a property for an absentee landowner to clear a path along the perimeter of the property. He hadn't shown me the property lines, but I thought I figured it out from the mapping app I use. I was unsure about the west line where there were two parallel fences. Many woods were once pastured here, and field lanes often have a fence on either side and sometimes along the property border. I studied it a bit and noticed that the outer fence lined up with the center of the road that turned in there. It seemed logical to me and I was unable to immediately contact the owner to confirm, so I went ahead and cleared the old lane, which had been cleared before but had since grown up. We finished the job and moved on, but a short time later, I received a call from the landowner.

A conservation officer had informed him we had taken trees from the neighbor lady's property. Thankfully, our client was a conservative Christian who cooperated with the investigation and shouldered part of the blame as he hadn't realized where the line was either. The owner and I met with the arbiter, a state forester (who I knew from Best Management Practices training) who appraised the logs. We had to pay the rightful owner three times the value in accordance with Indiana law. The logs were still in the field, so it was a simple matter to determine the value. There really weren't many trees taken from the lady's property (we were clearing an access lane, not cutting mature timber), and the logs were mainly small pallet logs. The total value was only $600. The forester gave the value to the neighbor, who admitted to thinking her ship was coming in and was disappointed, but she did accept it. The owner and I agreed that together we would pay her four times the value since:

1. We had wronged her.

2. The value was low.

3. We had removed some smaller saplings that had no market value.

4. It would be a way to go the second mile.

I do not know if we handled everything right, but it seemed to be satisfactory to everyone involved. I hope we showed that we were not trying to take advantage of anyone. Again, this could've turned out far worse—at least it didn't go to court.

Trespassing

Quite frankly, it is impossible to stomp around the woods as much as loggers and timber buyers do and not accidentally trespass from time to time. Around this area, most woods have old woven or barbed wire fences around them, but the old fences are rusting away to the point of being impossible to find. As mentioned above, old fences may not be a reliable indicator of a property line, although they are usually correct. Setting foot on someone's property by mistake is as inevitable as it is illegal. How can we avoid accidentally trespassing?

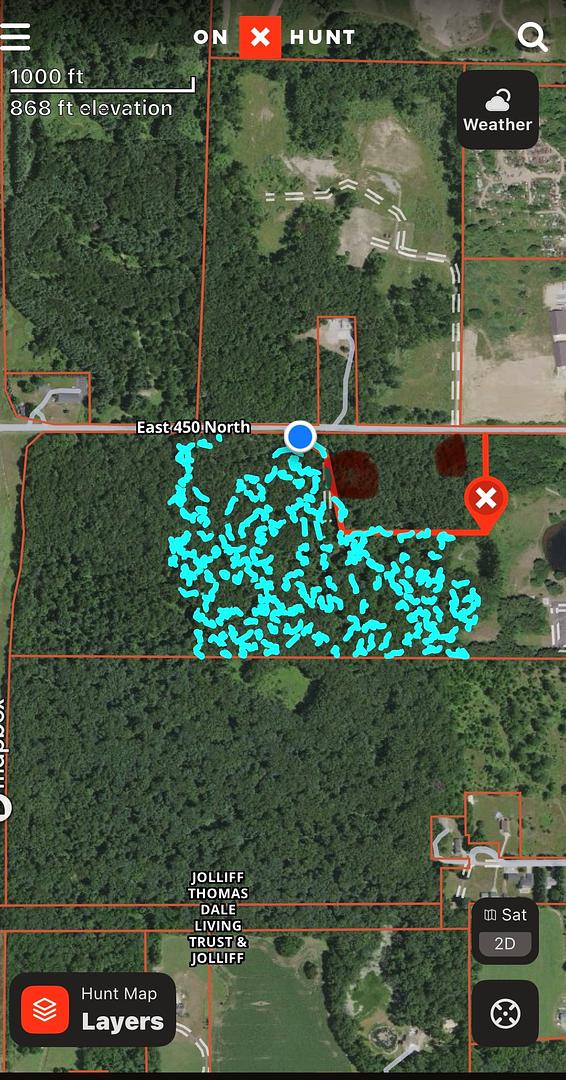

Delineating the property line is technically the responsibility of the landowner, but there are situations where the owner doesn't know exactly where the line is, or even worse, believes the line is somewhere it is not. We use the onX Hunt app that shows both property lines, and your real-time location. It is not super accurate but can get you within about ten feet, which is usually close enough to find old fence, a rusted off post, or a survey pin. However, this app is not always correct about lines, which is partly what got me in trouble in the incident above. The state forester told me there is no map that is 100% accurate; the only way to confirm a property line is by consulting with the landowners on both sides of the fence or by having a survey done.

It is common to see trees growing right on the line with the fence going through the tree. As I understand it, such a tree belongs to both owners and may not be harvested without mutual consent. The income from a fence tree would be split unless the owners reach some other agreement about who owns it. I have seen two neighbors walk their property line and agree that "you own this one; I own that one" rather than sharing ownership. Good neighbor relationships smooth a multitude of problems!

I heard of a situation recently where an unscrupulous timber buyer was looking at timber on a property and noticed some desirable trees on the neighboring property. He walked across the line and marked several Walnut trees. He apparently had no trouble with tree identification. It seems every jockey has an eye for Walnut trees. He then went to the landowner and said, "I accidentally crossed the line when I was marking your neighbor's woods and saw some trees I'd like to purchase." His lie became apparent when it was discovered that he had the property line properly marked—he knew right where the line was. It might have been more believable had he marked only a few trees near the line, but that was not the case. Trespassing situations like this, not to mention high-grading immature Walnut, give the timber industry a black eye.

Takeaways

1. Good communication with landowners is paramount. Logging a woods without ever meeting the owner is unsettling. While the forester or timber buyer generally has accurate details from the owner, a few details sometimes slip through the cracks. Building trust with the owner involves the logging crew asking pertinent questions about the project’s goals to ensure satisfactory completion. For instance, in some circumstances I might knock over unmarked but hazardous dead trees as a favor for the owner, but if I know the owner is fond of woodpeckers, I would know to leave them. It goes a long way if the owner senses you care about his goals for his woods.

2. Contracting with companies or individuals lacking integrity can criminalize us or at least make us guilty by association. While using timber spotters may not have been illegal, it was unethical. As Christians, we should realize that civil law is not our moral compass.

3. My grandfather wisely advised, "As long as we continue to assume, we will continue to err." As I discovered, assuming the property line’s location can be costly. It is uncomfortable to run afoul of the law even if it is an innocent mistake. As imperfect humans, we will make mistakes, but let's not allow carelessness to give credibility to the prevailing distrust toward the timber industry.

4. Cooperating with law enforcement is our Christian duty, even if they treat us harshly over an innocent mistake. When I met with the arbiter, it seemed he was unnecessarily stern; but he was fair, and I was thankful for his arbitration.

As plain people, we view our land as God's land; thus, some of us may not view trespassing as a very serious offence. However, we do well to remember that aside from being illegal, it is also disrespectful to trespass on private property.

Ethan Royer, of Royer Logging, lives with his family in northern Indiana and provides logging services in northern Indiana and southern Michigan. He can be reached at 574.849.0867.

This article was originally published in Plain Communities Business Exchange (PCBE). Reprinted with permission. To subscribe to PCBE, call (717) 362-1118 or visit www.pcbe.us